St. Paul’s Catholic Church & Cemetery

Always Collecting the Pieces by Victoria Stuhr

Whether you’re looking at old photographs of people, animals, landscapes, or architecture, it is often easy to get consumed by a sense of nostalgia or wonder. In my case, it’s a relatively modest, Gothic style parish that ceased existing roughly 80 years ago. Understanding the Old St.Paul’s Catholic Church and Cemetery in San Pablo, California, has been a pet project of mine since 2015? it’s personal. Along with St.Mark’s Catholic Church in Richmond, St. Paul’s played a small part on my mother’s side of the family, who began their establishment in Richmond and San Pablo around 1917.

Relocating photographs of the Old St.Paul’s Catholic Church throughout the Richmond Museum of History and Culture, snippets of it online, or in the books created by the San Pablo Historical Society has been reminiscent of panning for gold and any lead I come across always feels like a “eureka” moment. One might not realize how many events and structural changes to the state of California that had to occur in order for this Church establishment to come to fruition. Some of the facts unearthed either contradict or strengthen the ones found before and I am fairly certain that this pet project will probably continue to be a part of my life for a long time, at least until I finally obtain a sense of clarity.

The Foundation – in brief

By the time Mexico had gained its independence from Spain by the late 1820’s, substantial damage had already been done to the Natives of the land that would soon become California. Contra Costa had been established as an offshoot of San Franciscos Mission Dolores. Its designated use was to raise cattle and cultivate foods for the Mission. The acreage was overseen by Francisco Maria Castro, a corporal connected to the Presidio of San Francisco who had come to the area with his family through the De Anza Expedition in the 1770’s.

After Mexico gained its independence, the changes continued as the new government ordered the Missions and the lands Spain inhabited to be turned over to the state. Massive land grants were then awarded to those who were loyal to the Mexican government. In 1823, just shy of 18,000 acres that comprised Rancho San Pablo were granted to Castro to use and he and his family resided over what would eventually become the cities of San Pablo, Richmond, El Cerrito, El Sobrante, and Pinole.

In 1834, a formal title was finally granted to Francisco Maria Castro by the Mexican government, three years after his death. Castro’s wife Gabriela inherited 50% of the land while their eleven children shared the rest among them. Gabriela would gain an additional percentage of the land after the death of three of her daughters and after her own death, her portion would all go to her living daughter, Martina. This would later on create a legal dispute between the remaining family members and a slew settlers who were trying to establish themselves in the area, many of whom were initially attracted here by the prospect of gold. It would not be until 1894 that a decree would be made that divvied up the land after decades of legal disputes.

Native California born Juan Bautista Alvarado served his role as governor of Las Californias from 1837 to 1842. He married Martina Castro in 1839, bridging a union between the two prominent families. In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed between the United States and the Mexican Republic, ending the Mexican-American War. That same year, the Alvarado family relocated from El Cerrito to the former adobe of Martina’s mother in San Pablo. By 1850, Contra Costa County was incorporated and California became the 31st state of the Union.

The Structure

True to their Catholic faith, the Alvarado family began holding special masses in the living room of their adobe, their piano serving as the altar. Clergy from Oakland and San Francisco would travel to the adobe to lead the services. Still, the growing community was looking for something more tangible.

It appears that the original St. Paul’s Catholic Church, located on Church Lane in San Pablo, came into fruition through a brief unity between a community requesting a place of worship and an Archbishop tasked with counteracting the lingering, religiously distasteful effects of the California Gold Rush by creating such establishments. It is also noted in an Oakland Tribune article from 1963 that St. Paul’s was initially founded as a Mission by the Old St. Mary’s Church of Oakland.

Juan Bautista and Martina donated between two to four acres to Archbishop Alemany in preparation to build a parish and on August 24th, 1864, a church edifice was erected where Alvarado previously had a great cross placed. The wooden parish itself was erected between 1866 and 1869, built with $600 raised by the community with Father Gualco as its first rector. In addition to the land, Martina also donated robes, an altar, and a chalice.?

In 1870, the Church obtained a bell, as well as painting of St. Paul by artist Virgilio Tojetti. The painting was delivered via sailboat from San Francisco by the son of Father Gualco and Henry Alvarado, son of Juan Bautista and Martina. These two objects that are still integral pieces to St.Paul’s to this day.

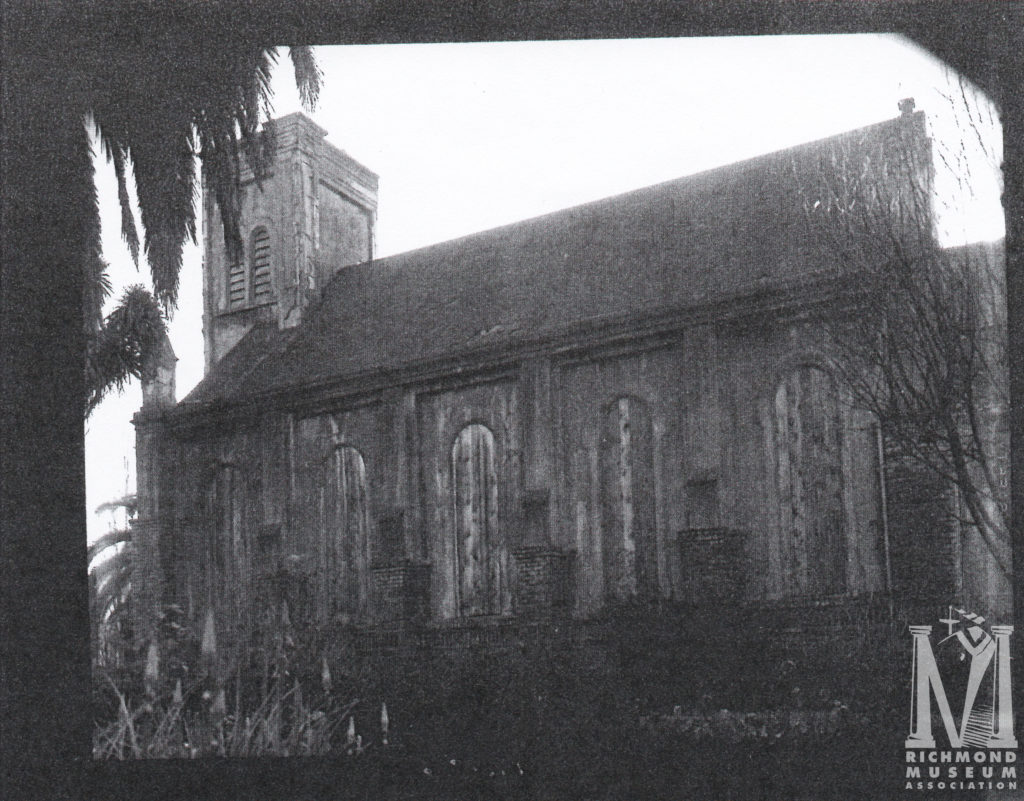

The Old Church’s architecture was not an uncommon design, yet it was still striking. The Gothic structure resembled that of the Old St.Mary’s Cathedral in San Francisco, as well as the other Old St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Oakland, all of which take after the cathedrals found in Spain.

Keeping with the old tradition, half an acre of land was dedicated for a cemetery that was used from the late 1860s until the late 1920s.

As the years progressed, St.Paul’s Catholic Church became a hub for San Pablo and the neighboring cities, mostly because it was the only Catholic Church in the area for some years. Festivities and fundraisers were often thrown? and local ranchers contributed live cattle or fresh meats for raffle winners. By 1912, street car services were maintained, with a round trip that transported people the church, down 23rd Street, to Macdonald Avenue, which totaled 20 minutes.

St. Paul’s Golden anniversary was celebrated on 1913. For 49 years, Patrick Fleming, the last remaining member of the original congregation, had passed around the collections plate during every service. He was also known for contributing $25 towards the Church’s original construction.? The next year brought on the Church’s 50th anniversary and all modes of transportation, from the streetcar Key System, to Southern Pacific trains or boats were available to get people to the celebration from neighboring cities. In 1916, St. Paul’s rector Reverend Father Porta helped the church obtain a shipment of Spanish Cedar and tile from Spain despite war blockades in order to build a new altar. Even as the structure started to show its age, it was still a place the community celebrated and utilized.

The Bay Area became a destination for the Portuguese, many of which hailed from the Azore Islands who were commissioned by US whalers and brought to the area after fulfilling their duty at sea. They often earned enough to buy their own land and built up their communities. For a number of years, San Pablo hosted the Azorean tradition of the Holy Ghost Festival.

In 1914, St. Joseph’s Catholic Cemetery was established on the same street on land donated by the Blume family, becoming the main Catholic cemetery in the area.

By the time the community began pushing for a new Church structure, St. Paul’s was the oldest Roman Catholic Church and Cemetery in West Contra Costa County. A campaign was started by Revered Father Porta and once again, the community helped raise the funds to build the St.Paul’s Catholic Church that you see today. In October 1931, the new building had a dedication ceremony presided by San Francisco Archbishop Edward J. Hanna. Descendants of the Castro’s provided an old fashioned barbecue, allowing attendees to feast on freshly cooked steaks from the Castro Ranch. The current Church quickly became a landmark of its own and it hopefully will continue to strive for many more years to come.

Although it was mentioned in an Oakland Tribune Article from October 26th, 1931 that the original parish was meant to be preserved, it was eventually torn down. The cemetery was also dismantled, making way for St. Paul’s School and a ball field, which would be added around the 1950’s. The Alvarado Adobe was also demolished in the 1950?s to make way for a new structure, but was rebuilt as a museum in the 1970?s. These conditions that surrounding demolition are where that longing feeling comes settling back in.?

According to a page on the Elk’s Lodge website, in 2012, Richmond’s Elks Lodge No. 1251 worked with parents and teachers of St.Paul’s School to refurbish the baseball field and install new planter boxes. It was noted that the ball field was once a cemetery and that although the remains that had once resided within the hallowed grounds were relocated in the 1950s, several buried stones were encountered? during the clean up process. This instance was not the first time something like that had happened.

The Tie

In the early 1990’s, the Richmond Museum came into possession of the headstone that currently greets visitors by the main entrance. It is a conversation piece, for sure.? A local family unearthed the headstone when they were working in their backyard and the discovery was understandably jarring for them. They searched for any signs of the bodies but only found bricks laid out in the shape of a cross a few feet below the surface.

The headstone belongs to Thomas Tormey and his sister, Mary. They were the children of local pioneer John Tormey, who made his way to California from Ireland and established himself as a landowner, rancher, supervisor, and business man alongside his younger brother, Patrick. The small company town, Tormey, between Rodeo and Crockett is named after them. Thomas and Mary Tormey do have burial records with St.Paul?s Catholic Cemetery, and their headstone had been relocated once the Cemetery was dismantled.

Along with the original church bell, the painting of St.Paul, as well as the rectory house and remnants of the cement and iron gate around the ball field, this headstone is one of the few visible signs of the original St. Paul?s.

The Tether

My fascination with the original St. Paul?s Catholic Church and Cemetery stems from the time my t?a told me to wave to my great-great grandfather, Melquiades, as we drove by the baseball field six years ago. It was the first time I fully realized the situation concerning him.?

My great-great grandfather, Melquiades Ba?uelos, came to the United States alone from Zacatecas, Mexico, around 1915 byways of El Paso, Texas, with hopes of escaping the Mexican Revolution. By 1917, he reunited with his wife, Maria, and their (at the time) four children. For a short time, they resided at the Southern Pacific Camp in San Pablo, a residence designated for laborers of the Southern Pacific Railroad. By January 1919, his life was cut short as he suffered from the complications caused by the Spanish Flu just nine days after contracting it. Three days later, he was buried at St. Paul?s Catholic Cemetery. To my knowledge, Melquiades is the only person from my family to have been interred there while a large majority of my family is interred at St. Joseph?s. His gravesite location was lost over time. During the Cemetery?s relocation, was he moved at all or was he forgotten??

I grew up frequenting St. Joseph?s Catholic Cemetery, my first experience with it happened in 1996 for the funeral of my grandfather, Miguel G?mez, who immigrated to the US from Jalisco, Mexico. He eventually settled down in Richmond by the early 1950’s when he married Maria’s Richmond-born granddaughter, Mary Rita Flores. I was not yet five years old when he passed away. The Cemetery visits started becoming a weekly ritual for my mom and me. Each visit, she started to remember where our other family members were buried and I slowly started to learn the histories of our rough past.?

My mom taught me about my great-great grandmother Maria, a victim of tuberculosis who passed away at the? notorious Weimar Joint Sanatorium in Auburn, CA. I learned about Maria?s children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, her second husband, and in-laws who are buried in different sections within St. Joseph?s gates.

But with this all said, I can’t learn about Maria’s first husband Melquiades because we can’t find him and his stories were not able to be passed down. Personally, I do not have any photos of Melquiades, just a reissued death certificate and a photocopy of his Record of Funeral from Wilson & Kratzer. Both documents prove his interment at St.Paul’s Catholic Cemetery, however the fact of not knowing where he physically is unsettles me. The reason I am a third generation Richmonder lies with him.

A similar situation has happened to another family, as displayed here on findagrave. The is also an incomplete list of the interments posted there as well. Do you know of anyone who may be buried in the cemetery at St. Paul?

Despite how many decades and generations have passed, the value of remembrance keeps our families alive.

If you have any comments or facts concerning the Old St.Paul’s, please feel free to reach out to the RMHC and share!

References and Supplementary Reads

- Bastin, D. (2003). Images of America: Richmond. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- Catholic Dignitaries See San Pablo Church Dedicated (1931, October 26), Oakland Tribune. Retrieved from newspapers.com?

- Celebrate 50th Year of Church (1914, August 12), The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved from newspapers.com.

- Cole, S.D. (1980). Richmond – Windows to the Past. Richmond, CA: Wildcat Canyon Books.

- Hansen, B. (1999). From a Rancho to a City Called San Pablo. San Pablo, CA: San Pablo Historical Society.

- House of Faith (1963, October 13), Oakland Tribune. Retrieved from newspapers.com.

- Knave: San Pablo Church Hits of an Alvarado Hacienda (1966, February 7), Oakland Tribune. Retrieved from newspapers.com.

- Passes Church Plate 49 Years: Fleming of Historic Congregation (1913, June 8), The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved from newspapers.com.

- San Pablo Catholic Fair a Big Success (1912, September 22), Oakland Tribune. Retrieved from newspapers.com.

- Smith, D. C. (2016). Stepping stones: the story of San Pablo, California, the last small town by the bay. San Pablo, CA: San Pablo Historical Society.

- Wood for Altar Brought From Spain (1916, October 19), Oakland Tribune. Retrieved from newspapers.com.